Driving under the influence of any drug is dangerous. It’s how people wind up dead, whether they’re in the driver’s seat or a passenger or in another vehicle. We are absolutely in favour of steps taken to reduce the chance of this happening, because we like our breathers breathing.

But the way it’s done must be scientifically robust and evidence-based. It has to at least, y’know, do the job it’s meant to do instead of being an expensive bit of security theatre.

What the current Coalition Government is suggesting is none of those things

In a move that made us roll our eyes out of our heads (again), the new National-Act-New Zealand First coalition has decided that they will enact legislation to roll out roadside drug testing using the same methods that the last Government suggested in 2022 and then rolled back in 2023, which we got extra spicy about. But this one has an added slice of unpleasantness in that traffic officers have a sample target number of 50,000 drivers a year.

Read the media release on Newstalk ZB

AA said that roadside drug testing works to reduce harm in Australia and the UK, so why are we mad?

AA voiced their disappointment at last year’s rollback, insisting that the technology works in other countries and didn’t understand why it can’t work here. Thing is, it doesn’t work in other countries. Even the Police said that the technology doesn’t exist anywhere in the world, and advised the Select Committee of this from the very beginning of proceedings in 2022.

Read the AA media release on their website

Read the statement from the Police Association President on the Newshub website

But don’t just take the Police’s word for it. We’ve done a bit more digging on top of what we did in 2022 when this legislation was floated the first time.

What does Aotearoa’s current legislation say about devices?

The approved devices in the current Land Transport Act 1998 71G haven’t been named specifically. There are a heap of interesting things in section 71G, but the ones we’re particularly interested in are:

- The Minister of Police is the person to give final approval on the devices used to run the tests, not the Minister of Transport.

- The Minister of Police has to consult with the Science Minister as well as the Minister of Transport when making the decision. They need to take into account things like

- accuracy of the device, and

- whether or not the device “will return a positive result only if the device detects the presence of a qualifying drug at a level that indicates recent use of a specified qualifying drug”. So, in effect, not throw false positives.

So even though the Minister of Transport can suggest roadside drug testing, all of the advisory research and so on has to go through the Science Minister and the Minister for Police before the device is approved. Keep that in mind when you read the next section.

Data still says no

The Ministry of Transport still hasn’t released anything about the kind of devices they’re going to use, but they’ve said they want to ‘bring things into line with what Australia is doing’.

This means that they’ll be using the Dräger DrugTest 5000 to do their roadside analysis. It’s the most sensitive machine that can be used from the back of a car and isn’t reliant on things like level surfaces and lack of vibration like the spectrometers we use are. It’s the most practical machine for the job.

We’ve had a look around the internet and only found one other roadside drug testing kit, which is the SoToxa Mobile Test System. It only tests for 6 substance types, where the Dräger DrugTest 5000 tests for 8, so we’re going to assume that the machine of choice will be the Dräger.

And before you ask, yes. The Dräger DrugTest 5000 is the exact machine that was proposed under the Labour Government in 2022. The machine that was deemed not sensitive enough for purpose and the one we got spicy about.

Australia

So as well as the false positives and calibration problems for the Dräger DrugTest 5000 we mentioned in the last blog, we found some evidence of false negatives.

High doses of THC give false negatives in both test types

Drug wipes and the Dräger DrugTest 5000 (the machine that would potentially be used in Aotearoa) don’t reach the 80% specificity level required for results to stand up in court. This means that they’re not accurate enough to give reliable results.

In a double blind study testing for THC in saliva with a 10ng/ml cutoff, the Drug wipes had a 16% false negative rate, and a 5% false positive rate. The Dräger DrugTest 5000 had a 9% false negative and a 10% false positive rate.

So that’s a total failure rate of 21% for the drug wipes, and 19% failure rate for the Dräger DrugTest 5000 when looking for THC. This does not fill us with confidence.

Read the study at Wiley Online

The numbers don’t add up

Our mates over the ditch have had over a year to prove that roadside drug checking reduces road fatalities. When we checked the Australian fatality numbers from 2018 onwards on the Transport Accident Commission (TAC)’s site back in 2022 they were all over the place with no clear trends. We checked again to see what’s shaken loose in the last couple of years.

We don’t really know what’s causing the road deaths in Australia. But roadside drug testing has been in effect in Australia since 2004, so you’d think there’d be signs of consistent reductions, if it worked.

| Year | Fatalities | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 211 | |

| 2021 | 234 | +23 |

| 2022 | 241 | +7 |

| 2023 | 295 | +54 |

Source: TAC website

We couldn’t find the stats relating to drugs and/or alcohol on the TAC website that wasn’t behind a paywall, so there could be any number of reasons for the increase in vehicle deaths. However if roadside drug testing is the solution it’s meant to be, we would hope to see a reduction in the number of deaths. We didn’t.

Britain

The National Police Chiefs’ Council’s media release said that in the lead up to New Years 2023 traffic officers performed 6,237 “drug wipes”, of which 53.6% showed positive.

The tech is still not accurate enough to give results that would stand up in court.

The question of false positives that we found in the Australian study still remains. The UK uses the same wipes as Australia, so those have a 21% failure rate. The UK’s ‘drugalyser’ is the The Dräger DrugTest 5000, which again has a 19% failure rate.

The data in their crash postmortem reports shows drugs very rarely present in fatalities

The reports concerning drugs and fatal collisions on the UK’s Department of Transport only go up to 2021, but what they do have is interesting. It shows that maybe people are looking in the wrong place when it comes to the causes for road fatalities.

It gets pretty granular so we pulled the numbers for

- Drugs and alcohol under the legal limit

- Drugs and alcohol over the legal limit

- Drugs and alcohol more than twice the legal limit

- Drugs and alcohol present but levels unknown

- Drugs and alcohol present but only in trace amounts.

And yes, there is a legal limit for the presence of substances both illicit and medical in the bloodstream for drivers in the UK. And it isn’t zero, either.

| Drugs present over or under the legal limit? | Alcohol present under or over the legal limit? | Total number road fatalities due to drugs and/or alcohol 2014-2021 | % of all road fatalities 2014 – 2021 due to drug and alcohol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under | Under | 99 | 1.3 |

| Under | Over | 65 | 0.9 |

| Under | More than twice the legal limit | 101 | 1.4 | Under | Trace levels | 374 | 5.1 |

| Under | Present, but levels unknown | 43 | 0.6 |

| Over | Under | 7 | 0.1 |

| Over | Over | 8 | 0.1 |

| Over | More than twice the legal limit | 7 | 0.1 |

| Over | Present, but levels unknown | 2 | 0 |

| Over | Trace levels | 50 | 0.7 |

| More than twice legal limit | Under | 67 | 0.9 |

| More than twice legal limit | Over | 113 | 1.5 |

| More than twice legal limit | More than twice legal limit | 147 | 2 |

| More than twice legal limit | Present, but levels unknown | 19 | 0.3 |

| More than twice legal limit | Trace levels | 351 | 4.8 |

| No drugs reported | Under | 403 | 5.5 |

| No drugs reported | Over | 164 | 2.2 |

| No drugs reported | More than twice legal limit | 329 | 4.5 |

| No drugs reported | Present, but levels unknown | 523 | 7.1 |

| No drugs reported | Trace levels | 2,918 | 39.8 |

Source: UK Department of Transport

So the category with the most fatalities is the one with no drugs reported (59.1% in total). Not any of the ones with high levels of drugs, medium levels of drugs, or low levels of drugs. And yet drugs are meant to be high risk when it comes to driving and a major cause of death? Drugs have been the monster under the bed that everyone needs to fear since the early 1900s, so we guess it’s easier to blame them than do some rigorous research into what those other causes could be?

Something we heartily approve of is that they have a legal limit for substances. This weeds out substances that would be used in therapeutic settings like opioids (pain relief), stimulants (ADHD, hay fever), Z drugs (sleep adjustment), etc. when they’re present in therapeutic dose levels. This also detection of a substance days after the person’s taken their drugs easier to ignore.

What’s even more interesting is the data feasibility report written on the back of this research, to see if the kind of data being collected was useful. For research to be robust and stay relevant it’s always a good idea to check that you’re gathering the right data.

This report showed that yes, the data are solid, but they had some recommendations:

- Add a data category showing whether ‘Query Psychoactive Drugs’ were administered before or after the crash.

- Query psychoactive drugs are substances like morphine, fentanyl and other strong painkillers that paramedics are allowed to use in the course of helping someone on the way to the ambulance. This is important because if someone tests positive for something like opioids, ketamine, or benzodiazepines they could have been administered by ambulance offers for pain or stabilisation en route to the hospital.

- If the substances had been administered by ambulance officers it wouldn’t count towards a drug-driver fatality

- Do a literature review looking at Query Psychoactive Drugs in historic toxicology reports

- This would establish how often query psychoactive drugs were administered by emergency staff

- In turn, this would help current and future researchers figure out the probability rate of Query Psychoactive Drugs being administered during first aid or recreationally

Both of these measures would make the data a lot more precise, and you all know how we feel about precise data (we love it).

Read the full report (PDF, 926KB)

Reddest of red flags: There’s an annual quota for tests.

According to the news release there’ll be an annual quota of 50,000 tests. So that’s 50,000 people pulled over for a spit test per year.

We have STRONG misgivings about this because

- At the moment the procedure is that people that are pulled over have to fail the Compulsory Impairment Test (CIT) before they are required to take the kind of test that requires blood/saliva. If there’s pressure on traffic officers to meet a quota instead of relying on their own judgement, how many people will “fail” the CIT just to meet numbers?

- This is overkill. According to the Ministry of Transport’s website, there were 1,266 crashes in 2022 ranging from minor fender-benders to crashes where someone has died (again, still waiting on 2023 data). The number of collisions is about 2.5% of the number of people that are going to be pulled over in a completely fair and not at all racially-profiled/age-profiled manner

- We already know that Maori and Pasifika are disproportionately targeted in “random” roadside checks (we got salty about it in the OG roadside drug testing blog) and this gives a racist system another avenue to be racist in.

One of AA’s complaints was that the traffic officers would have to do the CIT, which ‘takes time’. To which we can only say yes. Establishing impairment DOES take time. You know why? Because not everyone who drives dangerously or erratically is actually intoxicated to the point of impairment. (Yes, we too were shocked. Shook to the core)

Officers need to know if the person they’ve pulled over is intoxicated, they’ve got the sun in their eyes or they’re having a record sneezing bout, their vehicle is malfunctioning in some way, or they’re just driving like a dick. This way the officers know how many demerits to issue and get their admin correct.

Going straight to a spit test is going to be an even bigger time-sink because the officers will have to chase up the person once the spit test is done, and also apologise for treating the driver like a criminal before actually establishing whether they are one or not.

Read the current legislation dictating who needs to take an oral fluid test (Land Transport Act 1998 71A)

Read the ABC News article researching police quotas in New South Wales (CW police brutality, racism)

We’ve already had this conversation.

When we heard about the Labour Party planning to roll out roadside drug testing in 2022 it raised a BUNCH of red flags for us. These were (in no particular order)

- The tech used in roadside drug testing isn’t sensitive enough to differentiate between prescription medications and illicit substances

- The ‘science’ behind roadside drug testing is based on a correlation = causation fallacy that doesn’t stand up to rigorous investigation

- The ‘science’ behind roadside testing also doesn’t take into account that certain substances stay in your system for days after you’ve come down and are no longer impaired

We got extra spicy about it because we thought it was a terrible idea then. You can imagine what we’re feeling now.

Read the spice from 2022’s roadside drug testing proposal

In March 2023 Labour rolled back the roadside drug testing idea because the drug testing technology that would give results that would hold up in court didn’t exist yet. This was a bit of a relief, but there were aspects of the roll-back that we got spicy about.

Read the spice from 2023’s roadside drug testing roll-back

What’s changed since we got spicy in 2022?

Nothing.

This magical new spit-test machine that would provide solid evidence that would stand up in court? To the best of our knowledge, it still doesn’t exist.

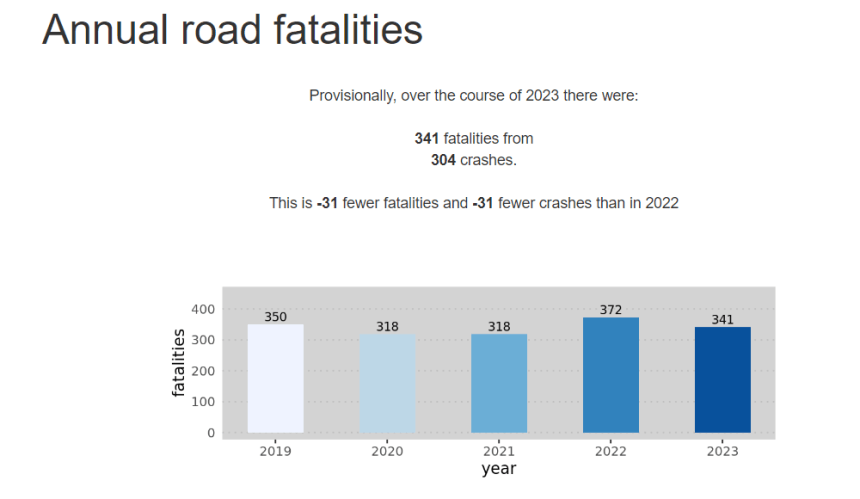

Te Waka Kotahi hasn’t updated their crash analytics as far as causes of fatalities, but we do have a number of people that died on the roads for 2023. And it’s lower than the number of people that died in 2022.

So if it didn’t work then, and it doesn’t work now, and it doesn’t work anywhere in the world, why the hell are we doing it? Especially if the road toll is dropping without roadside drug testing being rolled out.

Things that the taxes being flushed down the toilet on this could be better spent on to lower road deaths

The taxes we pay go towards things like infrastructure, education, healthcare, and a slew of other things. This legislation is part of the bit of infrastructure that looks at roads and transport, so affects the budget that would go towards things like road repair, signage, public transport, and so on.

Is roadside drug testing going to be good value for money?

No. No it’s not.

We couldn’t find the cost for a single Dräger DrugTest 5000 unit in NZ dollars without asking for a quote. We’re not going to do that, so we took the price from a UK website and converted the cost from pounds stirling. This gave us a unit price of $9,107.17NZD. Per unit. If the roadside drug testing initiative is going to have the coverage it needs to net the 50,000 tests to clear the annual quota, we’re going to need a fairly large amount of these machines.

Also, the Dräger units have a shelf life of 16 months. So they’ll need either servicing or replacement after a year and a bit. This initiative is going to be really expensive for something that has a 19% failure rate.

What could the Coalition spend our tax money on instead?

A nationwide reliable public transport system

People drive while under the influence of drugs and alcohol because it’s an option that’s affordable and easy. Having a cheaper option available that people could actually rely on to get them home might encourage people to leave their cars at home. We won’t know until we try, right?

Improve the barriers and signs on rural roads and tight corners

While we were doing the research for this piece we went through the coroners’ reports for road deaths published between 2022 and 2023. There were 58 reports published in that time, but of those, only 6 people died between 2020 and 2023 and everyone else in the reports had died before 2020. N=6 is far too small a sample for good statistics, so we couldn’t really use those numbers for the period that we’re looking at to challenge roadside drug testing as it is currently being proposed.

However there was a strong thread through most of the historic reports and some of the current ones where, when someone went off the road, it was in a place where there were no barriers, there was poor signage where they were driving to warn of things like blind corners, or a combination of the two. If you’ve driven anywhere on the State Highways you’ve probably seen at least one roadside cross with flowers marking where someone’s come off the road and died.

We should note that because the reports we read were historic, the conditions might have improved since the date of the person’s death, but it’s better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it, right?

We’re making a submission against this draft policy. You should too.

We’re not letting this pass without a fight. Feel free to let the Ministry know what you’re thinking about this particular piece of legislation too.

The submissions close on the 29th August, so you’ve got a little bit of time left

Have your say and make a submission on Parliament’s website.

We’ve also made a template if you want to make a submission but are stretched for time or mental/emotional bandwidth. Feel free to use the text below verbatim, or use it for inspiration.

Roadside drug testing submission template

Tēnā koe

I’m writing to you in response to the Land Transport (Drug Driving) Amendment Bill.

I have the following concerns and recommendations about the Bill in its current form:

- There have been no improvements in the device found to be unfit for purpose by the Labour Government in 2023 (Dräger DrugTest 5000 drug testing unit). They have a 19% failure rate due to the high level of false negatives, allowing people under the influence of drugs to stay on the road.

I recommend that this policy be deferred until technology is available that can produce reliable and effective results. - Some of the substances the drug testing units detect are prescribed by medical and psychological professionals (eg cannabis, ketamine, opioids, amphetamines, etc).

I recommend that the Committee considers allowances to account for people who have prescriptions for these substances. - The substances being tested for in the initiative stay in people’s saliva from 12 hours to 3 weeks, depending on the substance.

I recommend tests be put in place that determine level of impairment rather than assuming that presence of a substance automatically means a person is impaired. - The proposed penalties for people found to have drugs in their system due to false positives or prescriptions and are not impaired are unfair and can have significant impacts on their lives and employment.

I recommend that a form of financial compensation be put in place for any lost income due to these false positives. - Research done in the UK and Australia have shown that roadside drug testing does not lower the road toll. Any links between roadside drug testing and a reduction in collisions is specious at best, specifically in the study undertaken by Monash University.

I recommend that a full evaluation of the evidence linking road accidents with the presence of illicit drugs is undertaken, and that this policy be deferred until this work is complete. - Global research shows that setting quotas for the Police has resulted in negative impacts for indigenous communities as officers try to get their numbers up. Research in Aotearoa has shown that Māori and Pasifika are unfairly over-represented in the legal system across the board.

I recommend avoiding the use of quotas in relation to this policy, and additionally applying strict procedure to ensure officers’ personal biases do not affect the outcome of this policy.