In 2023, the province of British Columbia received an exemption from the federal government to decriminalise personal possession of certain drugs. The plan was to reduce opioid-related harm incidents with an overall goal of reducing opioid deaths. Within a year it was rolled back and considered by many to be a failure.

So what went wrong? Can decriminalisation work? Will it reduce drug related harm?

Spoiler, yes it can, if done properly.

About the exemption

The exemption decriminalised the personal possession of up to 2.5 grams (in total) of any of the following drugs: MDMA, methamphetamine, cocaine and opioid drugs like heroin or morphine. The pilot was meant to be three years long, ending in 2026.

Under the pilot it was still illegal to use drugs in school and child care premises, airports and motor vehicles, much like alcohol. It also remained illegal to sell and distribute drugs.

Police could initially offer health and social services, and only resort to seizure of drugs or arrest if other laws were broken or if the exemption was not adhered to. To support this approach, there were already a number of other health and social outreach initiatives in place, such as:

- Supervised injection sites

- Take home naloxone kits

- Lifeguard digital health app for overdose alerts

- Toxic drug alerts

- opioid substitution treatments

- Community action teams

- Drug testing sites

For full details of the pilot exemption, and the parallel public health response:

Subsection 56(1) class exemption to possess small amounts of certain illegal substances in the province of British Columbia – health care clinics, shelters and private residences – Canada.ca

For more information on these initiatives:

Naloxone DrugFacts | National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

What is opioid substitution treatment?

BC communities hardest hit by overdose crisis supported through community action teams, funding

It started well…

The initial months showed some positive results. There was an immediate spike in people accessing take-home naloxone kits, and a slower increase in people accessing other harm reduction services, like supervised consumption sites and drug testing services.

While there had been a significant decrease in the number of people being charged for drug possession, there was little difference in the rates of people dying as a result of taking any of the illegal substances in question. Fentanyl also still featured prominently in a high percentage of deaths (82% in 2023-2024).

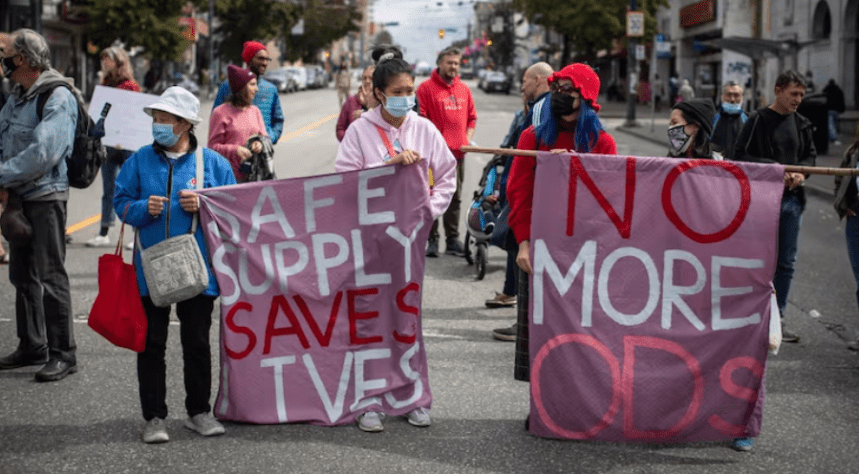

However, within the first year, many media outlets were reporting significant public backlash against the act, as people apparently reported increases in drug use in public places, including some instances of drug use around children.

While it isn’t clear how widespread these were in reality, it still led to a big response from local politicians, with many conservative political opponents using this as a way to criticise the current federal and local governments.

As part of the early campaigning towards the upcoming national election in October 2025, the primary conservative political candidate has indicated significant misgivings about the project and has even threatened to roll back other existing harm reduction strategies such as supervised consumption sites, which he referred to in one interview as ‘drug dens.’

This appears to have also impacted public opinion on drug decriminalisation. Public surveying showed a decrease in positive opinion of drug decriminalisation from the start of the pilot compared to the end of 2024.

And so, the province of British Columbia, ‘significantly roll[ed] back’ aspects of the exemption, thanks to pressure from the public and media, combined with influence of the provincial Police department, only eight months into the original three year timeline.

Despite the slightly misleading headlines, the change simply aimed to expand the number of public places where decriminalisation does not apply, particularly ‘child focused’ spaces like park playgrounds and skate parks.

Decriminalisation is still in place in private spaces, and some public spaces, like drug consumption sites and drug checking sites.

Following this change, they continued to see stable numbers accessing treatment, but most importantly, the death rates from illicit drug use did not decrease, with a record number of deaths connected with illicit drug use in 2023.

Key findings: Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada

Why the pilot in British Columbia didn’t meet expectations

We found a couple of problems with the pilot:

Problem #1: The roll back significantly reduced the effectiveness of the pilot

Strangely enough, saying people are allowed to do a thing, then saying they’re not allowed to do the thing makes for a fairly poor result, if you’re using people doing the thing as a metric.

Re-criminalising use of drugs in public spaces means that people are more likely to use drugs at home alone, or in other dangerous spaces. This puts them at greater risk of overdosing without anyone around to call emergency services or administer life-saving medicine. In particular, this affects people who are experiencing homelessness.

Read the Lancet’s article on the recriminalisation of drugs in British Columbia

Problem #2 The possession amount is too low for many people who use drugs regularly

“2.5 g, I could do that before noon”

Quote from drug user in recent qualitative study discussing the Act exemption

Regular drug users could have more than 2.5 grams of substances in their possession, particularly those who use more than one drug, and those that have a more severe dependence.

Many people who use drugs will buy multiple days worth of supply from the one dealer if they can afford it. This allows them to save money and time spent acquiring drugs, and allow them to wait to buy products from trusted dealers. If they have to buy more frequently, that limits the ability to use the same person, as they might not have product when the buyer wants it. This increases the chance that they might have to buy drugs from a new source with potentially riskier product.

Early consultation on the exemption with people who use drugs recommended that the amount be at least 4.5 grams. In Portugal the amount is set at 10 days of supply. This consultation was not listened to by legislators, thanks in part due to pressure from Police.

An act that does not seek to protect all substance users, does not adequately protect them from drug related harm.

For more information on the decriminalisation process in Portugal: Drug decriminalisation in Portugal: setting the record straight. | Transform

Problem #3 Police involvement in drug reform

You are probably not surprised to learn that people who use drugs often have difficult relationships with police officers.

There were concerns raised by people who use drugs that it might lead to police interacting more with people who use drugs to check that they are obeying the law. This could lead to more arrests for stepping out of the rules, or for other crimes that they might be involved with, rather than people being diverted into healthcare or support services.

Some people who use drugs said that they are worried that police might apply the exemption inconsistently, and that biases might be particularly noticeable in smaller towns or rural areas.

By including a strong police presence in this intervention, it undermines the shift from a legal/criminal response to a health care response, and highlights the problem of ‘mission creep’, where police take on tasks beyond their original role, that is noticeable in other aspects of society. Handling social issues or mental health crises that Police weren’t initially meant to address can lead to strained resources and a shift away from their core focus on law

Read this for an article that better unpacks this argument: Decriminalization or police mission creep? Critical appraisal of law enforcement involvement in British Columbia, Canada’s decriminalization framework – ScienceDirect

Problem #4 Decriminalisation of possession over other drug related crimes

Regular use of drugs to the point of dependence is usually expensive. People who use drugs and experience addiction are often marginalised by society, and may struggle to get or maintain a job.

Sometimes this is linked to having a criminal record for drug possession. This can force people to participate in other types of crimes like dealing, burglary, or theft to make money to survive. A policy that doesn’t address this doesn’t adequately target the problems that maintain drug addiction.

Problem #5 The drug exemption did not directly address issues with the toxicity of illegal drugs in North America

Canada is experiencing significant levels of fentanyl added to a number of different types of drugs. Coroner report data over the last few years has cited fentanyl as a factor in a high percentage of drug-related deaths, with numbers in the last several years ranging from 75-82%. This number is slowly increasing.

This exemption does not address the concerns of the safety of the drug supply available to those who use drugs. This has been less of a concern in other countries that decriminalised drugs before fentanyl became such a major problem.

In other words, people can possess drugs, but those drugs are still at risk from adulteration. So people are still taking drugs that have additional things like fentanyl in them, the only difference is that now they’re legally allowed to take them.

To dive into the coroner report data: Coroners service – unregulated drug deaths

Some drug users have also raised concerns about the pilot leading to increased clamping down on drug suppliers, which then increases the uncertainty of drug supply quality. If they lose access to dealers they have set up trusted relationships with because those dealers are arrested, this means the buyer has reduced access to a supply they know to be low-risk.

Dare to dream… drug decriminalisation, or drug regulation in New Zealand – could it be possible?

Many experts across the world agree that drug decriminalisation does work to increase positive outcomes for people who use drugs. This includes decreased rates of imprisonment for drug-related crimes, reduced stigma, and increasing people’s access to treatment.

For a discussion of the benefits of decriminalisation, as well as a discussion of the difference between decriminalisation and legalisation, see this article: Overview: Decriminalisation vs legalisation – Alcohol and Drug Foundation

So if Aotearoa wanted to consider decriminalisation (spoiler: we do), how could we make sure it succeeded?

Timing – programme may take a while to see positive effects

While some effects would be seen fairly quickly, a number of benefits won’t be evident straight away. Ideally the act would receive political support from all parties, so changes in Government wouldn’t lead to massive roll backs before we experience positive changes.

Improving health care services

Most experts agree drug decriminalisation won’t work on its own. Aotearoa would need to invest more in programmes like:

- addiction services,

- drug checking,

- take home naloxone kits, and

- mental health care

We’d also need to invest in the creation of other proven life-saving measures like supervised consumption sites.

A proposal by the New Zealand Drug Foundation estimated that comprehensive funding for health care and addiction services would cost about $150 million per year, and drug education would cost about $9 million per year.

It would save on criminal justice costs by an estimated $27-46 million per year.

Furthermore, if we adopted a hybrid model where we decriminalise all harmful drugs, and legislate or regulate cannabis use similar to what we’ve done with alcohol, we could use tax revenue raised from the distribution of cannabis to fund the cost of relevant health care improvements. This has been successful in other places (e.g. Oregon). This model has the potential to be cost-neutral to the taxpayer, with the added bonus of a lot less unnecessary human suffering.

Engaging communities who are more severely affected by harmful drug use will be vital in this process, including ethnic minorities and those in areas that experience more significant poverty. It turns out people who use drugs often have a lot of insight into what is helpful for them. Who knew?!

“Decriminalization is not a silver bullet. If you decriminalize and do nothing else, things will get worse. The most important part was making treatment available to everybody who needed it for free. This was our first goal.”

– João Castel-Branco Goulão, Portugal’s National Coordinator on Drugs, Drug Addiction and the Harmful Use of Alcohol General-Director of SICAD.

Removing historic drug convictions

In order to take this problem seriously as a health care issue, not a criminal issue, there would need to be quick moves to expunge the records of those who have existing drug possession charges.

Education and public support

In order to reduce stigma and misinformation, as well as increase public buy-in, money would need to be invested into drug education. While it may be easy for you, reader of this blog, to see the upside of decriminalisation, for many it will feel like a radical move, potentially in the wrong direction.

People need to understand the value of decriminalisation in order to support it. It is no small feat to roll back decades of misinformation thanks to the ‘War on Drugs’ that has captured the global mindset around drugs since the 1960s. More public buy-in will improve the chances of success of this policy, while also reducing the chances that politicians can start to use it as a political football.

Aotearoa has often blazed a trail on social issues. We have an opportunity to tackle one of the most complicated, important issues that society faces, and to try something new, while learning from the work of other countries that have come before us, and create a more just society in the process.

Bonus content:

Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 Needs to Go Part 1: How it started

The MoDA Needs to Go Part 2: The War on “Drugs”

The MoDA Needs to Go Part 3: How It’s Going

Drug Decriminalisation Across the World – TalkingDrugs

References

Ali, F., Russell, C., Greer, A., Bonn, M., Werb, D., & Rehm, J. (2023). “2.5 g, I could do that before noon”: a qualitative study on people who use drugs’ perspectives on the impacts of British Columbia’s decriminalization of illegal drugs threshold limit. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 18(1), 32.

Ali, F., et al (2024). Unpacking the Effects of Decriminalization: Understanding Drug Use Experiences and Risks among Individuals Who Use Drugs in British Columbia. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 190.

Fischer, B. (2023). ‘Drug decriminalization’ in Canada: a plea for a nuanced, evidence-informed, and realistic approach towards improved health outcomes. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 114(6), 943-946.

Greer, A., Zakimi, N., Butler, A., and; Ferencz, S. (2022). Simple possession as a ‘tool’: Drug law enforcement practices among police officers in the context of depenalization in British Columbia, Canada. International journal of drug policy, 99, 103471.

Greer, A., Xavier, J., Loewen, O. K., Kinniburgh, B., and Crabtree, A. (2024). Awareness and knowledge of drug decriminalization among people who use drugs in British Columbia: a multi-method pre-implementation study. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 407.

Xavier, J. C., McDermid, J., Buxton, J., Henderson, I., Streukens, A., Lamb, J., & Greer, A. (2024). People who use drugs’ prioritization of regulation amid decriminalization reforms in British Columbia, Canada: A qualitative study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 125, 104354.